By Dave Robbins

Microbes (bacteria, fungi, yeasts and other microscopic organisms) are ubiquitous in the environment, assisting in natural processes of decay and in the recycling of nutrients. This means that when they come in to contact with man and his environment, they can be a nuisance and they can cause deterioration in almost all products made with natural materials (essentially all items and materials originating from plants, including oils). That is to say, it is probably unsurprising that perishable goods will rot so the fact that other organic materials made of similar basic constituents will be similarly vulnerable to decay, if not specifically treated to prevent it. However, it might be surprising that some inorganic materials, such as steel and concrete, which might not generally be thought to be susceptible, are also prone to the potentially damaging effects of microbiological growth.

Microbially Influenced Corrosion (MIC) apparent as pitting in steel due to sulphide generating bacteria which can arise from poor maintenance of coatings and longstanding water or sludge.

Water that contains organic material, in longstanding contact with bare steel, can result in certain bugs (sulphide generating bacteria) that will cause accelerated corrosion of steel. Other bugs (sulphur oxidising bacteria) have been found to be responsible for corrosion and perforations in concrete sewer pipes. These bacteria and many other types occur in industrial processes and can cause problems such as blockages in recirculating systems, loss of lubricity, staining and bad smells which can affect machinery operation, the operators present or the value of finished goods. Products may become unsightly because they are cloudy, containers can swell or even burst due to gas produced and some microbes can, of course, pose health-risks, such as the presence of Legionella bacteria in recirculating water systems.

Disputes and claims can arise due to moulds growing in or on bulk produce, which is shipped and stored around the world in parcels of tens of thousands of tons or more. As grains and similar cargoes are often valued in excess of $300 per ton, the potential losses from mould contamination are significant. Certain national authorities can have specific requirements for produce being imported, ranging from the produce being fit for consumption through to strict limits on the concentration of mycological toxins such as aflatoxins or ochratoxins, or named organisms. Claims for spoilage of bulk produce frequently involve other costs associated with dealing with the matter such as delays, alternative storage and disposal (demurrage, salvage sale and other charter disputes with ships).

Factors that might result in microbiological contamination of bulk materials include the moisture content of the goods upon storage, alleged failures in conditioning or ventilation practices, water ingress, temperature changes and condensation. The cause of the damage can often be identified through the pattern of damage exhibited by the bulk material and knowledge of the growth requirements of the contaminating organisms. Products containing oils can, in some conditions, undergo chemical self-heating following on from microbiological heating, which in turn can lead to combustion. Many incidents of microbiological growth in produce stored in bulk are discovered by reports of smoke or the appearance of burned produce. These symptoms might be steam and blackened, mouldy cargo. However if not acted upon the symptoms could indeed lead to smoke and burnt produce!

Showing the range of discolouration of South American soybeans from sound to blackened.

Showing the range of discolouration of South American soybeans from sound to blackened.

Escapes of water or moisture ingress into buildings can lead to unsightly mould growth on the surfaces of the building or on and in their contents. The appearance of moulds can also lead to the occupants becoming concerned over their health, with mention of mycotoxins or toxic black mould. Such problems have arisen when, for example, drying and dehumidification processes following wetting (escapes of water or flooding) have not been thorough. The claims can comprise requests to replace costly fixtures or fittings in a building or even parts of the structure, as well as a “loss” of contents. Such claims tend to arise when the contaminant is grey or black water.

Other mould problems can arise when there is insufficient control of the temperature or humidity of the environment. Ventilation patterns or the building design can lead to elevated humidity, cold spots or condensation which if undetected will lead to surfaces and materials becoming colonised. The phenomenon can be commonly seen in the cold corners of humid areas such as kitchens and bathrooms. However, the problem can arise anywhere and affect the materials present if the temperature and humidity conditions are correct for growth.

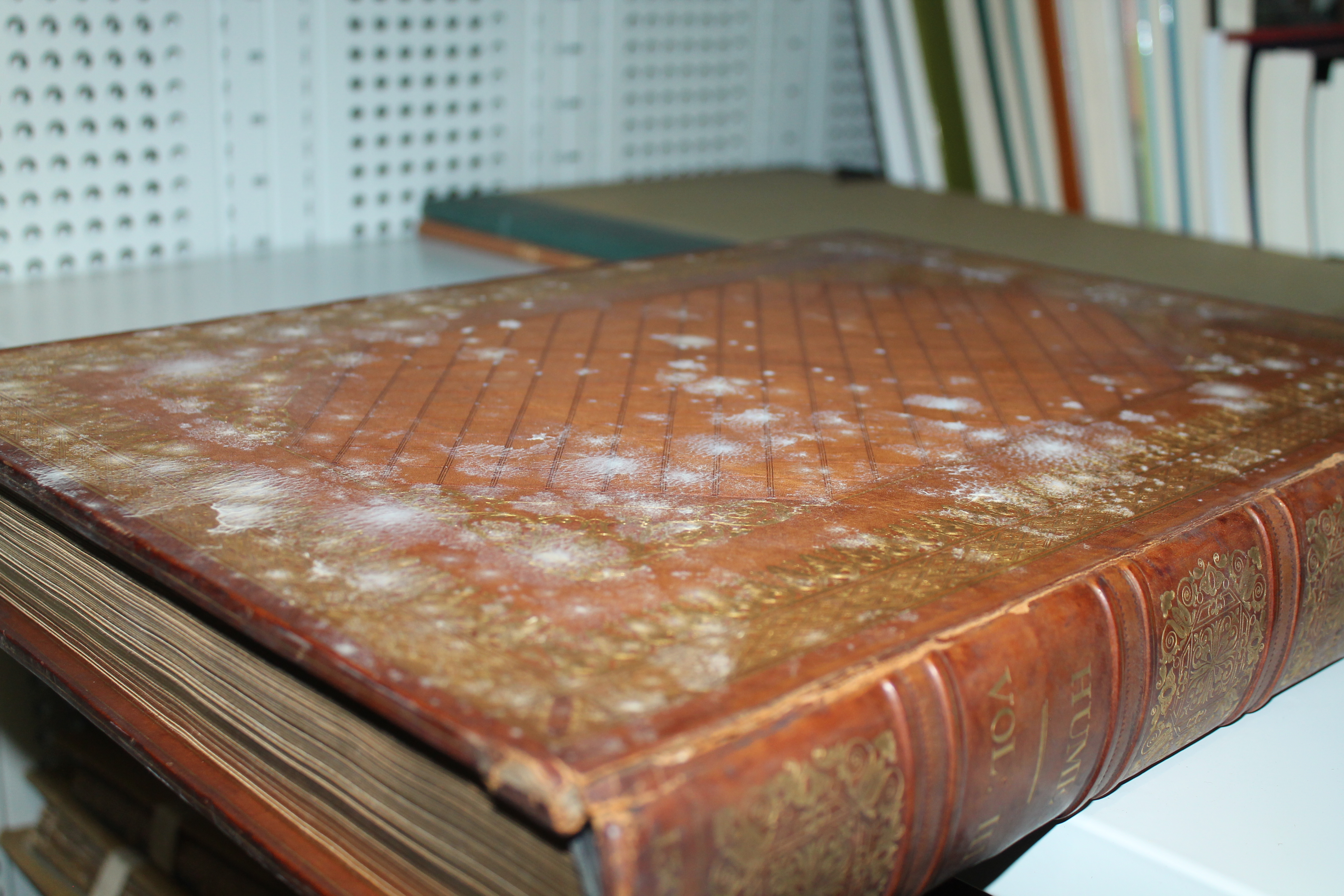

High humidity in an archive led to mould growth on historic books. Longstanding issues with the store and its ventilation system were identified.

A few examples of recent cases that have posed questions for insurers and others, besides those concerning bulk cargoes, include:

mould growth in the special collections archive of a university library due to ventilation and climate control (see photograph above)

significant claims for ill-health due to a concern over mycotoxin (fungal toxins from “black toxic mould”) contamination following attempts at remediation of an escape of water

identification of the cause of cloudiness that arose in a premium beverage during storage (see photograph below)

problems in reaching acceptable microbiological cleanliness in a pharmaceutical cleanroom

water ingress into a basement and foul water contamination of a floor void.

Cloudy deposits formed in a premium sparkling beverage. An issue with the in-bottle preservative was identified.

Cloudy deposits formed in a premium sparkling beverage. An issue with the in-bottle preservative was identified.

The matters dealt with raised questions such as potential health effects, whether controlled products would meet regulatory compliance, how the problem could be resolved, whether the problem was a processing matter (policy coverage), or long term natural deterioration (policy coverage), the adequacy of preservatives, the production methods and strategies and identifying the principal reason for microbial growth.

If you have a query over whether a problem might be microbiological or just wish to learn more please contact David Robbins at the Cardiff Office: +44 (0)2920 340047 or email him at david.robbins@burgoynes.com.